Reinventing food preservation: the evolution and future of food design

An interview with Sonia Massari

Food design, often seen as a recent phenomenon, actually has deep and complex origins rooted in the rise of industrial food production. Over decades, this discipline has evolved from engineering and preservation techniques into a comprehensive approach that intertwines culture, health, sustainability, and technology. In this interview, Sonia Massari (Please visit her website using this hyperlink) challenges common perceptions, exploring how understanding the true history of food design can shape innovative solutions and even promote longevity (a full interview on this topic can be downloaded via this hyperlink), ranging from smarter appliances to circular economy models, toward enabling a longer, healthier life for all and a more sustainable future.

You often challenge the common perception of Food Design as a recent discipline. Could you elaborate on its true origins and evolution?

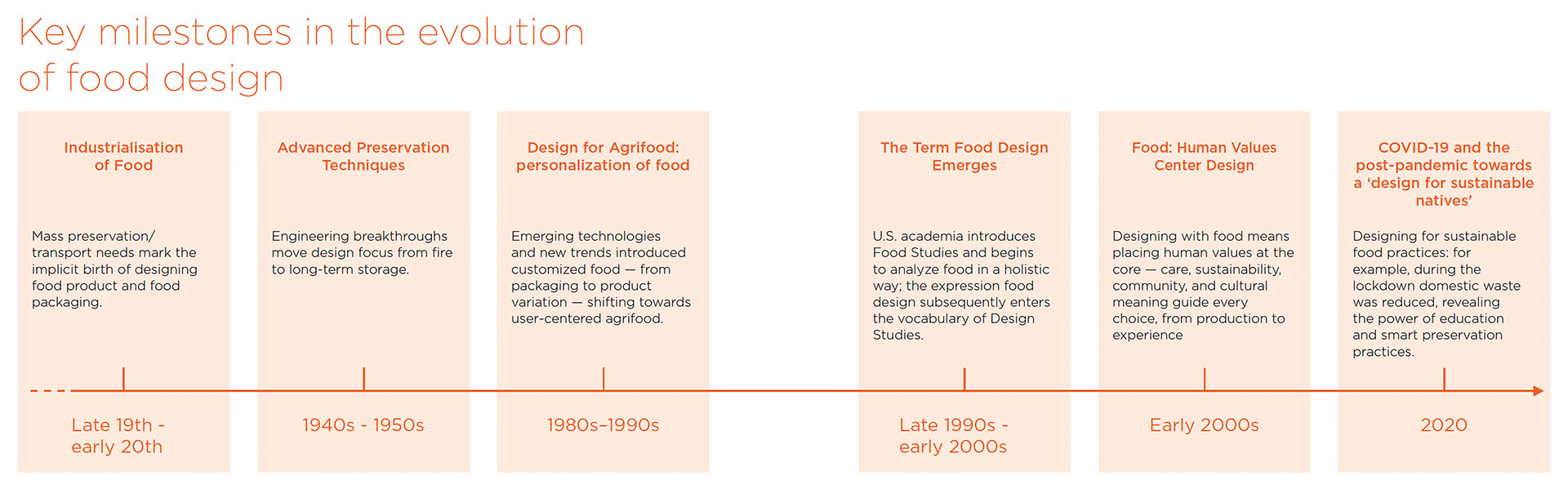

It’s crucial to dismantle the notion that Food Design is a new concept, something that only emerged in the last 20–25 years. The likes of Marti Guixe (a full interview on this topic can be downloaded via this hyperlink), Marije Vogelzang, and the Austrian pair Honey & Bunny pioneered the conscious and explicit use of the term “food design,” working to define it, set it apart from other terms and disciplines, and integrating it into their performances, work, and research. Yet, Food Design as a practice can be traced back to the industrialisation of food. The moment we needed to preserve and transport food on a mass scale, we inherently applied design methodologies.

Initially, this involved a significant blend of food engineering and design, a practical application of available expertise to ensure food preservation and efficient transport from production to consumption zones. This early phase, though not explicitly termed “Food Design,” laid the foundation for the mass production of food and the evolution seen from the 1940s and 50s, encompassing preservation techniques like desiccation, lyophilisation, and freezing.

The term “Food Design” gained traction in the last two to two-and-a-half decades. This is not accidental, it aligns with a pivotal historical period: the rise of Food Studies in the late 1990s and early 2000s, primarily in the United States. At that time, people started realising they were consuming unhealthy products, often poorly preserved. The drive for efficiency and cost reduction had led to mass-produced food lacking quality.

Civil society, particularly in the U.S., reacted strongly, pushing academic institutions to address these concerns: “Why are we eating things that are bad for us? Is the packaging healthy? Are the preservation techniques appropriate?”. This led to the integration of food culture and a systemic approach to food within departments previously focused solely on dietetics and nutrition.

As these Food Studies departments spread across American universities, the need to redesign food, from its conservation to its transport, became evident, leading to the incorporation of Design Studies into this process. Subsequently, this academic interest spread to Europe, with programmes akin to food studies appearing first in Pollenzo in the early 2000s, thanks to the Faculty of Gastronomic Sciences supported by Slow Food. In the same period, initiatives such as Gustolab International in Rome (founded in 2007, which I co-directed) contributed to consolidating this field, later joined by similar programmes across Italy and Europe.

So, the last 25 years represent a powerful combination: the systemic study of food by various disciplines (no longer siloed engineers, nutritionists, food scientists…) and the evolution of design from mere product design to a broader methodology encompassing product, service, system, as well as production process design and experience design. The most recent era has further integrated sustainability and health movements, pushing for more equitable and sustainable food processes and supply chains, ensuring food does not harm us, and most of all that it does not harm the environment, as the “more than human” approach is gaining increasing momentum.

You touched upon sustainability. While it’s a major topic, you suggest it’s not the primary driver for consumer choices. What do you see as the true underlying motivations, and how does design fit into that?

While sustainability is a very present and discussed value, and certainly a noble one, I believe consumers are primarily driven by health and longevity when it comes to food choices. People buy food because they want to live longer and better, because they want to be healthier. If a product offers the tangible benefit of an extended or improved life, individuals are often willing to invest in it, even if it means sacrificing aspects like social eating or perceived sustainability.

I often think about the future in terms of “sustainable natives”. These days, we’re born and bred in a world where digital technology is second nature. For those born today, no instructions are needed; they pick it up instinctively, use it from the word go, and often even manage to make it better. Likewise, I picture a world populated by sustainable natives: people who are born and brought up in an environment where sustainability is the norm, not a special case. A world where sustainable tools and practices are learned from a young age, feeling natural to use, intuitive, and straightforward.

In this way, sustainable technologies and behaviours become part of our cultural identity, internalised as key elements of daily existence. We’re not there yet; we still present consumers with a choice between a sustainable option and one that is much less so, but somehow more attractive. This suggests that the value of sustainability isn’t yet strong enough on its own to fundamentally shift our consumption habits. Sometimes, people adopt sustainable practices more to be part of a group than out of a deep personal conviction as the value of socialising, belonging, and the approval of others carries a greater weight and guides our behaviour.

Fermentation is gaining a lot of traction, both for its ancient preservation methods and as a modern food trend. How do you view its role, especially in the context of a circular economy?

Products like kombucha have indeed become “food trends” and “status symbols” over the last decade, particularly among health-conscious consumers. They align with the broader Food Studies movement where people are actively seeking information about what is healthy and beneficial. However, the current market positioning often sees them as a trendy, expensive item, sometimes disconnected from their fundamental utility in waste reduction.

Any chef committed to sustainability will tell you that fermentation is one of the primary forms of circular solutions they advocate. Having worked on a sustainable catering project serving 1500 meals a day, I can tell you that practices like “all-you-can-eat” present significant waste challenges. Fermentation of vegetables, fruits, and other products offers an economically advantageous solution for restaurateurs. It allows for the creation of new recipes and long-term preservation.

It requires skill, of course, as mistakes with bacteria can lead to very serious health problems, but these analog technologies should be fundamental knowledge for any chef. It’s a natural match for new consumption trends and sustainability goals, so I wonder why its broader adoption by industry for waste reduction hasn’t occurred more widely.

Speaking of waste, what are your thoughts on the global anti-waste movement, and the concept of “second-hand” food products?

While the primary emphasis on the “anti waste” movement, a commendable initiative, has been on environmental aspects, the principle of “One Health”, linking planetary health to individual well-being, is becoming more recognised. For instance, the Mediterranean diet, at its core, was a “One Health” diet, balancing food consumption with lifestyle and seasonal availability. However, our changed lifestyles mean that even the traditional Mediterranean diet of the 1950s wouldn’t be appropriate for us today due to differences in physical activity.

In terms of circularity and anti-waste, while people readily accept “recovery for sale” models like “Too Good To Go”, the concept of “second-hand” food products, like snacks made from food waste, is still largely invisible in the market, despite being discussed in academic literature for over a decade. Beer made from unused bread, for example, is more accepted because consumers perceive a clear, hygienic transformation process.

A powerful example that illustrates true circularity is Saltwater Brewery’s edible six-pack rings. This project addresses marine plastic pollution by creating rings from the very beer production waste. They are biodegradable and, crucially, edible for marine life. This innovation is a brilliant case because it brings together multiple stakeholders. The fisherman benefits because fewer plastics are harming marine life; the CEO is proud to invest in a sustainable solution, hoping others will follow; and the consumer feels good buying a beer that’s “good for me, good for the Planet”.

This demonstrates that true change occurs when all actors involved find a solution that is “effortless” and mutually beneficial. This also highlights a critical point: design has historically focused too heavily on the consumer side, the final stage of consumption, whereas it should be more actively integrated into the production phase.

For instance, when I met with a leading Home Appliances brand some years ago, I emphasised that if food production methods change, like the shift to regenerative agriculture or agroecology, then preservation methods must also change. A conventionally farmed product differs in preservation

needs from an organic one. Refrigerator manufacturers traditionally focus on consumer habits, like how often they shop, but less on “what is upstream”, how the food itself is produced.

Designers should look at the entire supply chain, from the sheep grazing on specific grasses to the final cheese product, to understand how changes at the origin impact the entire journey.

Let’s turn to the refrigerator, a central appliance in food preservation. How has its role evolved, especially considering recent global events like the pandemic, and what’s its future?

Manufacturers tend to analyse consumer habits meticulously: how often do people shop, how do they organise their fridge space, etc. However, they often overlook the upstream processes, how the food itself is produced and how that impacts its preservation needs.

One profound observation from the COVID-19 pandemic was a significant decrease in domestic food waste across industrialised countries, a reduction of 30–40%. This was counterintuitive, as one might expect more waste when people are forced to buy in bulk online or queue at stores.

However, reports indicate it happened for three main reasons:

Increased use of food preservation tutorials; People actively sought information on how to store food;

Improved shopping list habits; Consumers became more meticulous about planning their purchases based on actual domestic needs;

And enhanced cooking skills; People learned to cook better and utilise all parts of their ingredients.

This period was a unique, revolutionary learning experience where people self-educated out of necessity. As designers, we regret that we largely missed the opportunity to leverage these insights and design solutions, like apps for smart shopping lists or preservation techniques, that could have helped maintain these good habits postpandemic.

People quickly reverted to old behaviours.

This highlights a broader principle: design should learn from emergencies to project for the postemergency future. You don’t design during an emergency; you survive.

But you gather crucial data for future design. We failed to use that knowledge effectively

Looking at the refrigerator itself, I believe it should become an instrument of education. Many people lack basic knowledge about food shelf life or proper storage, how long a banana lasts, how to store open jars of pickles, or simply they have no clue as to what goes in the fridge and what stays out.

If the refrigerator can mediate between food production and consumption, understanding the nature of the product going in, it can educate the consumer.

This goes beyond just adjusting temperature or humidity, which are the current parameters, it means designing the internal space based on the type of food produced (e.g., how agroecology impacts preservation) and helping users understand how to best store specific items.

There’s also a fascinating psychological and even physiological need people have to open the refrigerator door. Even if you knowexactly what’s inside, there’s an addictive quality to this exploratory act.

This contrasts with industrial refrigeration, where closed systems are prioritised for efficiency and hygiene.

While appliance makers consider consumer habits, perhaps they haven’t tapped into this deeper human connection with the fridge as a source of discovery and comfort.

Could you elaborate on the “Open Meals Sushi Singularity Restaurant concept”, where food is specifically designed based on a body scan and DNA, and what this implies for the future of food?

Yes, the “Open meal” concept envisions a future restaurant experience that is hyper-personalised.

It’s a very interesting thought experiment:When customers arrive, at this hypothetic, futuristic restaurant, they get some sort of body-scan and DNA testing. Based on this scan, the food served is aesthetically perfect for you, as well as being the perfect nutrition combo for your individual requirements.

While such an experience might seem to promote eating alone, it addresses a critical future consumer need: eating “well” according to one’s physiological necessities, rather than just for basic sustenance.

This is a shift beyond the personalisation of the 90s.

The primary value for consumers is healthy longevity, the desire to live well and last longer, and they are willing to invest in food that supports this goal.

When I present this to students, they often voice concerns about the lack of socialising around this format because you eat alone.

They also try to find sustainability angles, like the absence of packaging this involves.

However, I view this sustainability aspect a bit off the concept, as the primary driver is clearly longevity.

This highlights a potential future where the desire for personal health and extended life will antagonise other considerations like socialisation or even sustainability in consumer choices.

Two very different points of view that will coexist in our daily future lives.

This concept also ties into the broader “One Health” principle, suggesting that if something is “good for me,” it is also “good for the Planet”.

This demonstrates how design in food is evolving, moving from simple preservation or product aesthetics to deeply understanding individual physiological needs and consumer values like longevity.

Considering all these shifts, what’s your vision for the future of Food Design and that of home appliances such as the refrigerator within this evolving landscape?

We need to recognise that the evolution of design and appliances is deeply intertwined with societal changes.

A prime example is a modular refrigerator concept from the early 2000s. It was aesthetically “ugly” by today’s standards and nobody bought it, but it was designed for “food on the move”.

It envisioned a world where people traveled more with low-cost airlines and trains, and might want to take their fridge module with them.

While the instrument, the portable fridge, wasn’t adopted, the underlying need for “food on the move” was brilliantly foreseen and manifested through food delivery services. The designers of that fridge understood the reality perfectly but perhaps misinterpreted the precise tool by which that need would be met. This illustrates how our lives have become increasingly mobile: mobile phones, mobile computers, and now mobile food.

In some advanced research contexts, the refrigerator’s role has already diminished to primarily chilling beverages. This is because food delivery has become so pervasive that people buy single portions as needed, making the fridge almost redundant for food storage. This, paradoxically, can be an “advanced” form of waste reduction: buying only what you consume. While single-portion trends might fluctuate, the idea of a minimalist fridge for modern living has been explored since the 1970s.

My definition of food design is “design for food and by food”. To create truly effective design solutions, designers must profoundly understand food itself. This deep research, which I advocate should be 70% of the design process, allows us to identify core values that drive behaviour change, rather than merely following trends or marketing directives.

The future of design in this space should involve designing the entire food supply chain – from seed to consumption.Imagine if digital monitoring systems in agriculture could connect with home appliances, providing consumers with complete transparency about their food’s origin and production. People today are deeply concerned about what they eat, where it comes from, how it’s produced, if it’s truly beneficial for their health and longevity. If a product or system provides this clarity and assurance of a longer, healthier life, people are willing to invest in it.

Design serves as a dialogue tool. It bridges the different “languages” and needs of various actors in the food system, from farmers to distributors. It’s about starting from what the refrigerator is not: the food itself, the values people hold, their behaviours, and then redesigning the fridge as a mediation and educational instrument based on those insights. This holistic approach, from understanding deep-seated human needs and societal shifts to integrating technology across the entire food chain, is where the true new frontiers of food preservation and design lie.

Bio

Dr. Sonia Massari is a highly accomplished expert with over 20 years of experience in Food Design and Innovation, human-food interaction, Sustainability Education, and the Co-Creation and Co-Design of innovative agri-food systems.

She holds a Ph.D. in Food Experience Design from the University of Florence, with a dissertation on the role of digital technologies in food systems. Her extensive academic career includes directing Gustolab International for 13 years, the first academic institution entirely dedicated to Food Studies Abroad, and serving as Academic Director for University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign Food Studies in Italy.

Dr. Massari has designed and coordinated over 50 academic programs and more than 150 place-based initiatives on food and sustainability for prestigious universities globally. She was a scientific advisor to the Barilla Foundation from 2012 to 2023 and in 2021, co-founded FORK Food Design Organisation, which is the world’s largest non-profit international platform dedicated to food design.

Currently, she is a researcher at the University of Pisa, Department of Food Agriculture and Environment, focusing on human-food interaction and participatory design methods, while continuing to teach Food Design at numerous national and international institutions. Her work has garnered multiple awards and recognitions, including the Tecnovisionarie, Women Innovation Award and the ASFS Pedagogy Award.

www.soniamassari.com

Food Preservation — A Homa White Paper

Food preservation is one of Homa’s enduring pillars — alongside Care and Design — shaping how we interpret our mission and how we envision kitchens, technology, and modern living.

Food Preservation as a Systemic Vision

Through the Food Preservation White Paper and our dialogue with global thought leaders, Homa translates research, field evidence, and design practice into a shared language for innovation — from precise temperature management and airflow engineering to user-centred solutions that extend freshness, reduce waste, and build trust over time.

As this conversation expands beyond engineering into culture and systems thinking, preservation becomes more than performance — it becomes meaningful value for families, partners, and the broader food ecosystem.

Editor in Chief: Federico Rebaudo

Editorial coordination & design

Studio Volpi srl

Federico Gallina

Pierre Yves Ley

Jacopo Porro

Copyright © Homa 2025

All rights reserved

Printed copies are available upon request through your usual Homa commercial contact.

Copyright HOMA 2026- Issued By Homa Marketing dept. on January 2026

For further Information and Press Contacts: info@homaeurope.eu